As a variety of products seek to utilize high-performance stainless steel grades with increased corrosion resistance, extreme temperature resistance, and durability in both critical and non-critical environments, it has become increasingly difficult for manufacturers to use conventional processes alone to efficiently produce unique stainless steel parts in high volumes.

By Kirk Gino Abolafia, Technical Marketing & Sales Manager, Voxel Innovations

While tougher stainless steel grades containing exotic materials (such as nickel, chromium, or molybdenum) offer unique advantages compared to other grades, these properties simultaneously create difficulties for many conventional manufacturing processes, such as CNC machining or broaching. These machining difficulties exist across austenitic, martensitic, and duplex steels, and a wide range of stainless steel grades, such as 316L.

Advanced alloys often wear down tools quicker — affecting the speed and the precision of processes attempting to machine stainless steel components in higher part volumes.

In response, design and production engineers around the globe are exploring alternative manufacturing methods that can reduce costs, including tool replacement, and postprocessing. One promising alternative is called pulsed electrochemical machining (PECM), a non-thermal, non-contact material removal method, capable of superfinished surfaces, high repeatability, and small features on metallic parts.

Limitations of Conventional Processes

Conventional manufacturing methods can produce high-quality, tight-tolerance features in most grades of stainless steel, however, with some limitations. For example, electrical discharge machining (EDM) utilizes spark ablation to remove material and can produce tight-tolerance parts with a surface quality (generally around .6-.8um Ra, or 23-31uin) sufficient for most non-critical applications. However, as EDM strips material off the workpiece using high temperatures, the removed material can sometimes re-weld itself back onto the workpiece. This ‘recast layer’ can result in surface abnormalities including microcracks affecting the part’s lifetime and durability.

Metal additive manufacturing (AM) has limitations such as its inability to produce high-quality surfaces without a secondary postprocessing operation. This problem becomes more acute when producing parts in critical environments that undergo thermal or fatigue stress or have critical flow requirements. Some surface irregularities are inherent to AM; for example, support structure remnants create surface abnormalities, and AM’s resolution usually decreases in ‘down skin’ areas or internal aspects.

Ultimately, it is difficult for many conventional manufacturing processes to affordably produce tight-tolerance stainless steel parts in high part volumes. While some processes can produce high-resolution stainless parts, it is often prohibitively expensive to replicate these features in high volumes. Simultaneously, many high-volume processes are incapable of producing complex features on high-performance parts without a postprocessing operation. However, in some cases, PECM is capable of machining high-volume, tight-tolerance parts, even on advanced, abrasive stainless steel alloys.

PECM is an advanced material removal process that does not utilize contact or heat. It is a newer, improved version of electrochemical machining (ECM) that utilizes a pulsed power supply. A custom tool is developed for each project, and the material is dissolved—and removed— by an electrochemical reaction carried by an electrolytic fluid that is flushed between the tool and workpiece.

To better understand the process, there are four key terms to comprehend:

Cathode: The cathode, or tool, is a custom-machined part that is shaped as the inverse of the desired geometry to be machined.

Anode: The anode, or the workpiece takes on many forms. It can be wrought stock, a near-net shape, an AM part, and more. However, the anode material must be conductive; PECM is incapable of machining plastics or polymers.

Electrolytic Fluid: Typically a salt-based electrolyte, the electrolytic fluid that is flushed between the cathode and anode during PECM serves two crucial roles simultaneously. First, the fluid acts as the conductor for the electrochemical reaction to occur. Secondly, the fluid acts as a flushing agent, removing waste products (including the dissolved anode material).

Inter-electrode gap: Also referred to as the IEG, the inter-electrode gap is the microscopic space between the cathode and anode where the fluid runs. PECM’s precision is largely dependent on the size of this gap; as PECM advances this gap continues to shrink; current technology allows this gap to be 10-100um Ra (.0004-.004in.)

Ultimately, there are four unique advantages of PECM technology. As the process uses an electrochemical reaction, and is not reliant on heat or friction to remove material, the hardness of the workpiece is not relevant to PECM, allowing it to machine nickel superalloys at a similar speed to copper.

Since there is no contact between the tool and workpiece, there is little-to-no tool wear in PECM, providing it high repeatability; with PECM can machine thousands, or tens of thousands, of identical parts without incurring tool replacement costs, repeatability down to <10um (.0004 in).

Ultimately, there are four unique advantages of PECM technology. As the process uses an electrochemical reaction, and is not reliant on heat or friction to remove material, the hardness of the workpiece is not relevant to PECM, allowing it to machine nickel superalloys at a similar speed to copper.

Since there is no contact between the tool and workpiece, there is little-to-no tool wear in PECM, providing it high repeatability; with PECM can machine thousands, or tens of thousands, of identical parts without incurring tool replacement costs, repeatability down to <10um (.0004 in).

The removal rate of PECM scales linearly with surface area of the electrode. Put another way, with the right tooling, PECM is capable of machining multiple features in tandem (such as micro drilling holes, or channels in a heat exchanger), allowing faster machining rates than conventional processes.

PECM produces no surface irregularities, such as burrs or recast layers, creating a mirror-like surface quality on a variety of tough materials without requiring any secondary machining; PECM can create surfaces down to 0.005-0.4um Ra (0.196-15.748uin).

However, there are important caveats and limitations of PECM to consider. While PECM is capable of machining almost any conductive metal (from copper to Inconel), it is incapable of machining non-conductive materials, such as plastics or polymers.

Furthermore, PECM has higher NRE costs compared to other conventional processes, as developing the ideal cathode (tool) is a considerably complex process and requires multiple iterations of parts. This high initial investment is only outweighed if the project requires high part volumes (such as a nitinol fixture plate operation producing over USD $200K in parts annually). Therefore, PECM is not ideal for low-volume/rapid prototyping projects.

Stainless Steel Applications

Corrosion-resistant stainless steel continues to be a dominant material choice for many applications. Many design and manufacturing challenges associated with stainless steel machining overlap with PECM’s capabilities.

Part miniaturization is important for medical device manufacturers for several reasons, such as smaller, less invasive medical implants improving patient mobility. However, it can be difficult for conventional processes to affordably and efficiently produce small stainless steel devices, especially in complex geometries.

For instance, material removal processes that utilize heat and/or friction have inherent drawbacks that become increasingly problematic as part sizes decrease; tool vibration and heat distortion are common drawbacks that limit the precision capabilities of many conventional processes, including electrical discharge machining (EDM).

When machining pockets in surgical stapler anvils, they are initially coined/ stamped to a rough shape while the stainless steel is in a softer, annealed state to increase machining and reduce tool wear, then hardened again prior to a finishing operation in order to achieve final tolerance. However, hardening causes distortion in the metals (requiring additional machining) and sometimes the process itself can distort the product. Furthermore, re-fixturing the part in the machining cell after hardening can cause additional challenges, as the datum structures have been moved or distorted.

Another manufacturing obstacle associated with machining stainless steel devices is producing high surface quality, which is important for several reasons, including the fact that smoother surfaces are more sterile. Improved surface quality also reduces the risk of forming microcracks, corrosion, or chips, which could result in part failure

However, even if the device has excellent surface quality, other properties play a role in durability and sterilization; one study comparing two surgical devices with otherwise identical features and surface finish found that the 316-grade stainless instrument had enhanced antimicrobial and anti-corrosive properties, compared to the 304-grade stainless device.

Some conventional manufacturing processes are incapable of producing surface qualities that meet or exceed industry standards without utilizing a secondary postprocessing operation. Simultaneously, the processes more capable of producing adequate surfaces generally cannot reproduce these features efficiently in higher part volumes—and for some processes, this can become more challenging with tougher grades of stainless steel.

Heat Exchanger Applications

While some reasons differ, many engineering challenges plaguing manufacturing industry are applicable to heat exchanger manufacturing, including within the biomedical, aerospace, and chemical processing industries. These challenges (specifically, producing low-tolerance, high-repeatability features on advanced materials) are especially important for critical, temperature-extreme environments in the energy and aerospace sectors.

A design challenge largely unique to the aerospace manufacturing industry, for example, is called lightweighting—design and material choices optimized to minimize weight while simultaneously preserving their form, fit, and function.

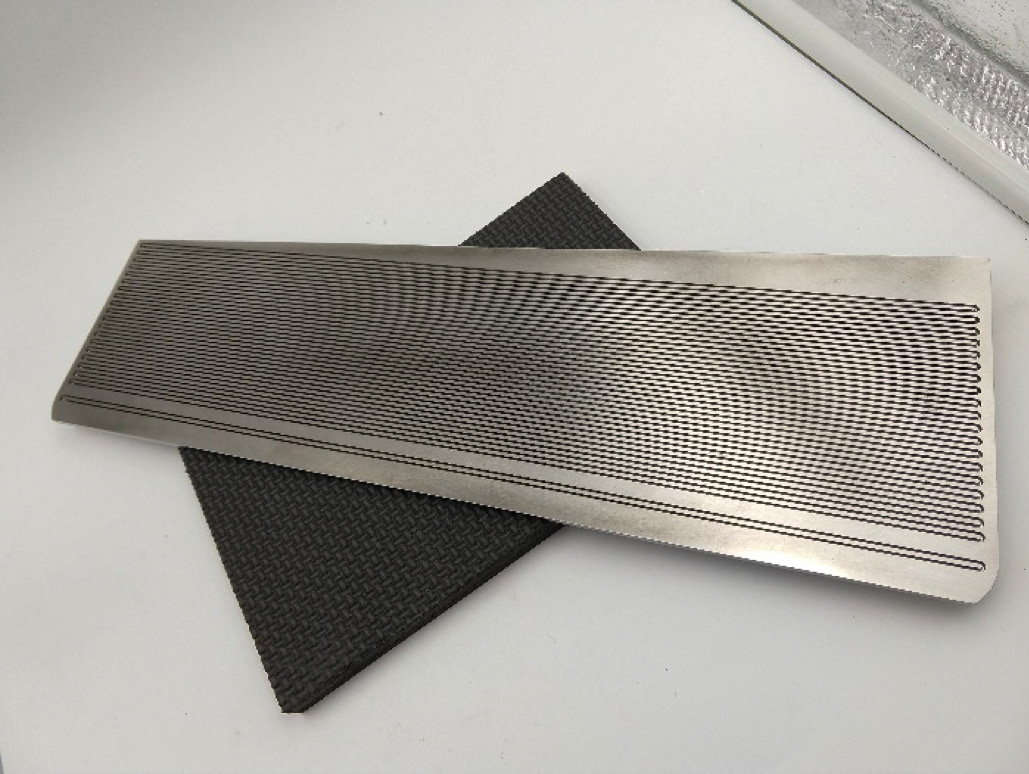

Microchannel heat exchangers in aerospace applications require lightweight features, high aspect ratios, thin walls, and tight spacing to maximize efficiency, however these features can be difficult to produce, as the small spacing and thin walls are difficult to both produce and replicate with conventional methods.

For example, consider how conventional processes machine thin microchannel walls. Both tool vibration and heat from the process itself can create distortions in thermally sensitive, thin-walled aspects of a part. Furthermore, surface irregularities inherent in some manufacturing processes often occur, (including burrs and recast layers) impacting the part’s functionality.

PECM, however, is ideal for machining small heat exchanger features. PECM does not inflict any thermal or mechanical stresses on the part, so thinner walls and smaller channels can be created, allowing improved heat transfer abilities and better lightweighting. As a single PECM tool can produce multiple features in tandem, the process can produce microchannel features with high repeatability hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of times.

High-heat flux applications often require tough-to-machine alloys that are difficult to machine with conventional processes, including superalloys and refractory metals. Fortunately, as PECM relies on an electrochemical process rather than friction or heat to remove material, exotic alloys used in critical heat exchanger applications can be machined sometimes as easily as aluminum with PECM.