As a young engineer, Chris Cary quickly realized he had a natural talent for ‘hands-on’ engineering. He maintained his positive, long-term approach to problem-solving throughout a rich career, during which he gained experience in fields such as nuclear materials, polymers and chemicals. Although officially retired he remains professionally active, including working as an inspector as well as participating in ASME and NBIC.

By KCI Editorial

Young engineers setting out on their careers would do well to take a leaf from Cary’s book: be curious, find lasting solutions, and discover where your true passion lies.

Cary started his working life back in 1988, at the DuPont (later Westinghouse) Savannah River Company. Development at the site started in the early 1950s, to produce the basic materials required for the US’s nuclear defense programs. This was a very interesting environment for an inquisitive engineer and gave cause for self-reflection.

“My first assignment there was project-related, but it soon became evident that sitting in the office working on schedules and estimates was not my thing. I quickly fell into working with the plant and operation folks, helping the operators and mechanics to do their jobs well. That resulted in a job change, moving into operations support. My official title was custodian, a position which gave me responsibility for much of the physical plant,” Cary said.

Cary recalls working on important projects such as ensuring the safe, long-term storage of waste materials. “For example, the company developed sequestration techniques whereby hazardous material was encased in glass. The idea was to lock in the waste matter, preventing it from escaping into the environment.”

Although the work was interesting, after a few years he decided to transfer from a government-controlled sector to private industry. He found employment with a rayon-producing company before landing at Dow Corning’s Carrollton site in 1996 (which became Dow Chemical in 2016). Although he retired from Dow in 2021, Cary continues to remain actively engaged with the company, conducting inspection work for Dow via quality assurance provider Intertek.

Root Cause

During his tenure at Dow, Cary’s focus was again on supporting operations activities, a position which brought along a huge and varied workload. “On any given day there could be multiple requests for assistance from operations. I therefore normally started by reading the overnight shift reports to assess where my intervention would deliver maximum benefit. Then I would head out to liaise with the operations or maintenance crew allocated to that job,” he said.

In addition to providing day-to-day support, Cary was also involved in long-term activities such as mechanical integrity and turnaround planning, as well as projects. “I helped to identify where the capital budget would be best spent, identifying whether it should be allocated to buying spare parts or to finance replacement projects,” Cary explained.

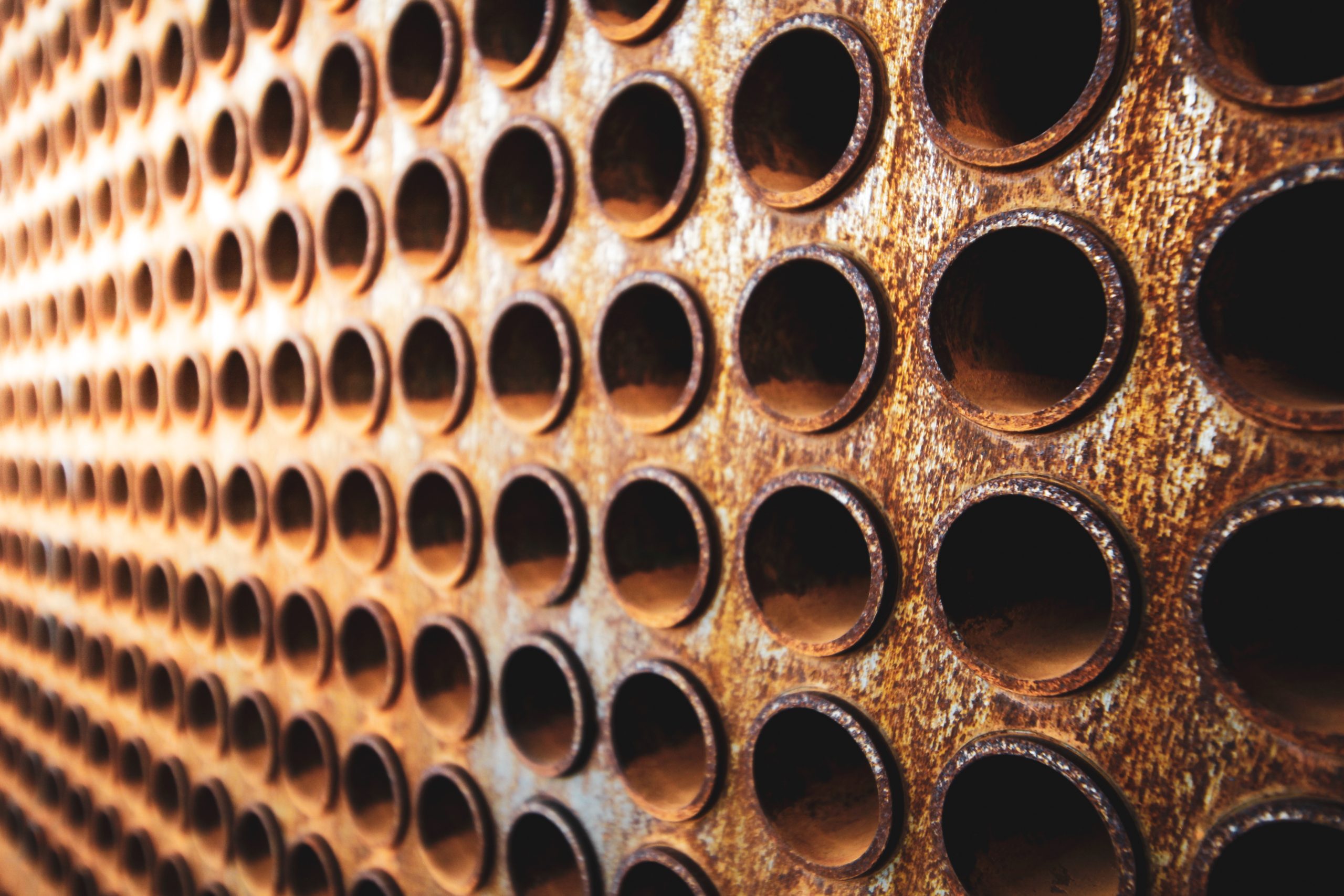

Thanks to his natural curiosity, Cary gained considerable expertise in equipment such as heat exchangers and fired heaters. “If a furnace trips, the first thing to do is to safely get it back online. But the job does not end there. The next step is to figure out the root cause of the upset and determine how to prevent any recurrence.”

Graphite heat exchangers could be a particular cause for concern, he notes. “They are delicate items. Even tightening the fasteners on them can be problematic if the job is not performed correctly. I have been known to skip meetings to check on and give advice to maintenance crews. Making sure critical jobs are done properly—and thereby ensuring plant uptime—is an engineer’s key function.”

Knowledge Management

Despite the many mechanical issues that Cary has worked on during his career, he is adamant that the biggest technology-related challenge in a plant is not a tangible one. “Knowledge management is key. By that, I mean the issue of understanding where technical information and expertise reside and how to maintain it and apply it. That is why engineers should develop a deep understanding of the technical processes in their plants and then pass along the insights they have learned by mentoring younger colleagues, for example. Knowledge must be embedded within the organization so that it can withstand staff turnover.”

On the topic of personnel changes, Cary stresses the obvious drawbacks if people decide to move elsewhere—even internally. “I have mentored many very bright and capable engineers, only to see them choose a different career path. Of course, everyone has a right to develop as he or she chooses, but it seems that young engineers are often tempted to switch to a management career. The question companies therefore need to ask themselves is: how can we keep people on the technical career path? Appropriate rewards and incentives are part of the answer but opportunities to grow professionally—such as having time to participate in relevant associations, budget to continue learning, and opportunities to assist in standards bodies—are just as critical.”

Knowledge Sharing

Cary is aware that in some circles, there seems to be an expectation that a ‘brain drain’ can be met by relying on equipment suppliers. “It is often said that the vendors have unparalleled expertise as regards their own products. To be fair, I have worked with some companies who employed real experts whose decisions I could rely on. But I have also seen vendor-supplied systems that frankly did not provide the expected functionality. Now, throughout my career, my goal has always been to help improve the overall organizational performance of my company. And, in my opinion, maintaining relevant technical knowledge and competence within the company is the best way to ensure the plant’s long-term productivity and safety.”

Having said that, Cary stresses that engineers—and even seasoned engineers—cannot be expected to know everything. Previously unknown mechanisms can occur in any sector, and the important point is to respond calmly and professionally. “First, solve the problem, then identify the cause, and, finally, freely share the lessons learned. Your colleagues, your employers, and fellow engineers around the world will thank you for it,” said Cary.

Professional Avenues – A Two-Way Street

Asked what advice he might give to an aspiring engineer, Cary replied, “Try to factor out your unique work style and how you can best contribute to an organization. Are you more suited to the technical ladder or the management ladder? Do you prefer project work or day-to-day activities? Office work or hands on? Determine your own personality, strengths and interests and see what opportunities exist where you could make a maximum difference for your employer.”

Cary also highly recommended participating in codes and standards organizations like ASME, API, NBIC, and so forth. “Doing this means they will be contributing to producing better standards. Plus, they will improve their own ability to correctly apply those standards and raise the value of their work. My involvement was kick-started when facing performance issues with flanges and gaskets. That led me to participate in the ASME subcommittee addressing flanged joint assembly. Later, I also joined the ASME subgroup looking at graphite pressure equipment. And I am still active today.”

Finally, Cary stressed the value of continuous learning. “Don’t ignore challenges—try and resolve them. And keep up to date by reading technical articles, engaging in technical discussions with the authors, and attending events.”

Growth Mindset

Cary addressed the difference between phrases ‘fixed mindset’ and ‘growth mindset’. The term ‘fixed mindset’ is used to describe an individual who views intelligence as essentially unchangeable and talent as a fixed commodity; this type of individual is someone who relies on his or her pre-existing knowledge when faced with new issues and is incapable of absorbing fresh concepts. By contrast, a ‘growth mindset’ describes someone who sees challenges as opportunities and is open to learning and applying new skills.

“Tapping into your natural curiosity and drive to realize improvements is important for an engineer,” stated Cary. “Over many decades I have seen production locations improving their practices in so many ways and in so many aspects thanks to people with a growth mindset. That includes areas such as operations, maintenance, new equipment fabrication, turn-around planning and execution, and so forth. Without question, there will always be pressure to improve performance. I see that as a good thing.”

Cary links this philosophy to knowledge sharing. “Is technical knowledge a fixed commodity for which engineers should be in competition with each other? Or is knowledge something that is nurtured and grows when we collaborate? I truly believe everyone is better off if we share knowledge with our colleagues but also with peers working elsewhere. People who protect their own domain can – however unintentionally – cause harm to the companies they work for. So, keep learning, stay in dialogue with others and don’t shy away from high expectations.”