A new technique is allowing researches to track microscopic changes in metals or other materials in real-time, while exposed to extreme heat and loads for an extended period of time.

The technique, demonstrated by researchers at North Carolina State University in the U.S.A, will expedite efforts to develop and characterize materials for use in extreme environments.

Until now, you could look at a materials structure before exposing it to heat or load, then apply heat and load until it broke, followed by a microstructural observation, says Afsaneh Rabiei, Corresponding Author of a paper on the work, and a Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at North Carolina State University. That means you would only know what it looked like before and after loading and heating.

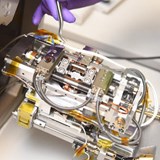

This technique, which is called in situ scanning electron microscopy heating and loading, allows researchers to see the microscopic changes taking place throughout the process. You can see how cracks form and grow, or how microstructure transforms during the failure process, Rabiei continues. This is extremely valuable for understanding a materials characteristics, and its behavior under different conditions of loading and heating.

Rabiei developed the in situ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technique for high temperatures and load (tension), with the goal of being able to predict how a material responds under a variety of heating and loading conditions.

The instrument developed can capture SEM images at temperatures as high as 1,000°C, and at stresses as high as two gigapascal which is equivalent to 290,075 pounds per square-inch.

For their recent demonstration of the techniques potential researchers conducted creep-fatigue testing on a stainless steel alloy called alloy 709.

Creep-fatigue testing involves exposing materials to high heat and repeated, extended loads, which helps us understand how structures will perform when placed under loads in extreme environments, Rabiei explains. That is clearly important for applications, which are designed to operate for decades.

After performing a specific test that looked at alloy 709s behavior in a nuclear reactor over many years, researchers saw that the alloy outperformed 316 stainless steel, which is currently used in many reactors.

Our observations showed that when a crack reaches twin boundaries in alloy 709, it redirects itself and takes a detour. This detouring effect delays crack growth, improving the materials strength. Without our in situ SEM heating and loading technology, such observations could not be possible, says Rabiei.

Moreover, using this technique, we only need small specimens and can generate data that normally take years to generate. As such we are saving both time and the amount of material used to evaluate the materials properties and analyze its failure process.

Image courtesy of Aerospace Testing International