3D printing and additive manufacturing have been gaining traction in the metal industry. Many companies are looking for new and innovative ways to not only prototype and test, but produce different parts, materials, and more. Stainless Steel World Americas spoke to Jonah Myerberg, Chief Technical Officer of Desktop Metal, to learn more about their new alloy, DM HH Stainless Steel (DM HH-SS): what it is, how it is made, and how it can be welded and used in various applications.

By Sara Mathov

Desktop Metal, a 3D printing company, has come out with a new custom material; DM HH Stainless Steel. Desktop Metal is a 3D printing company, aiming to make 3D printing accessible to all engineers, designers, and manufacturers. Founded in 2015, the company combines experts in manufacturing, metallurgy, and robotics.

What is DM HH-SS?

“DM HH-SS is what we refer to as high hardness stainless steel, and it is a unique alloy,” said Myerberg. “It is similar to other stainless steels that are out there, but it has properties to make it tougher and harder than some other grades. With this, of course, comes some compromises. It has a bit less corrosion resistance compared to others, yet still some, but the market we are after is one where toughness and hardness are desired.” Common applications that would benefit from this material are tools, automotive, and the oil and gas industry.

Applications that are best suited are tough components where you need strength and hardness. “A downhole tool that needs a lot of resistance, hardness, and strength would be great for this material. We are finding that a lot of lower grades are heat treatable, can perform similar to 4140, and offer some corrosion resistance, and that is very attractive to our customers. Many 4140 customers start to use 17-4 PH, and are very happy with the fact that it does not oxidize, or rust, but they still need a bit more of the strength that 4140 shows. That is where DM HH-SS came in, because we were able to really push up the strength, and enable heat treating,” he said.

The main benefit, according to Myerberg, is that it includes the properties of milder carbon steels like 414 0, yet still retains elongation, similar to softer stainless steels. “It still has some corrosion resistance, so you end up with a working steel with hardness properties and weldability.”

Besides tools such as those that break up concrete, requiring toughness, and adding corrosion resistance allows for further use of the material. In marine applications, steels can oxidize if you get salt spray on them. This leads to rust, and plating wearing off.

Therefore, the oil and gas industry could see great benefits from using this material. “Fracking sites have significant salt content that they pull out of the ground, which may be why a stainless steel would not be used in those applications. For anything in contact with fracking fluids, this material could step in and offer toughness to survive the application, and avoid dying as quickly because of corrosion.”

How is it Made?

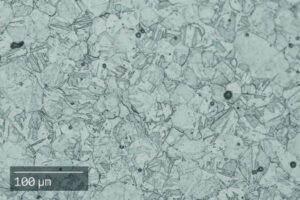

“Our printers use powdered metal that is very fine. Our process, called binder jetting, includes taking this powdered metal in a layer as thin as 50 microns, and jetting a binder glue onto that layer. This is repeated, spreading thin layers, eventually forming a three-dimensional part. Then, you take that part out of this bed of powder and put it into a sintering furnace, where the heat drives out all of the porosity of the powder. The part is now a fully dense steel component. The grains grow larger than the powder, so one would not recognize that it came from a powdered metal process,” said Myerberg.

The company works with suppliers of powder, who have been making metal powder for decades. “We have many approved powder manufacturers, some in the U.S., and some in Europe and Japan. Many powdered metal foundries can mix up steel with the recipe you want,” said Myerberg. “They then spit it through a small opening, and spray it with high pressure gas or water, which is called atomization. There are many atomization plants around the globe that we work with, creating good competition, and allowing us to find suppliers that are best suited for certain steels or precious metal. We will buy standard materials, like 316, but we can also request slight variations to the metals, allowing us to explore the printing process.”

The supply chain disruption has impacted the powdered metals industry like any other throughout the pandemic, but not as much for raw materials as it has for shipping. “It has been a good thing that we have powder suppliers close to home, but trade routes have been a struggle.” With 3D printing comes the opportunity for stainless steels to be used in unique applications where it might not normally be the first choice. “It enables new applications and designs. We have a tool, 3D printers that can print stainless steel, and we ask our customers what they would do with it, and they run wild.”

“At the end of the day, the parts that come off of our printers are just like the parts that come from traditional manufacturing processes, and can be taken through all of the traditional finishing processes as well. It is identical in the chemistries to that of traditionally produced stainless steel. You end up with a piece of the puzzle, and no matter how how the parts are produced, what is done with them afterwards in terms of shining, polishing, plating, hardening, is all up to the user.”

Welding DM HH-SS

Myerberg said that this material is very weldable. “Not all materials are. It has to do with the grain structure and crystalline structures formed during the heat treating process,” he said. “Many alloys, such as 718 Inconel, are very difficult to weld, simply because the heat-affected zone will cause cracks. Once you weld, you could be changing the properties in that welded area, and potentially require another heat treat. Therefore you may want to do a weld before the heat treat strategies.”

Welding is very alloy specific, and each alloy that is printed is similar to any alloy that you can buy traditionally. “The same welding concerns translate no matter how the part or material is manufactured,” said Myerberg. “Through the printing process, we include what is called a sintering process. This is where after the part has been printed, it goes through a high temperature inert gas fi re, which consolidates it and drives out all of its porosity. This makes it a fully dense part with no stress left. Sometimes, with welding processes, stress can be released or imparted into the part through the weld. So, a benefit of a part off of a printer is that it is stress free, which is a great starting point to begin a welding process.”

With disruptions from supply chains, many customers are considering additive manufacturing and producing the parts themselves. “In Michigan right now, we are exploring this. Both 3D printing and traditional manufacturing have been around for a long time, so it will be interesting to see which applications are best suited in either direction, or perhaps a combination of both.”

“The reason I think 3D printing is growing as rapidly as it is, is because it enables new applications to be explored very quickly. Not only does it allow users to do things they have not done before, like create different geometry with unique features, it allows them to do it quickly and without a large investment in tooling. Users can take digital or virtual ideas, very quickly bring them to reality through printing, and test them. That is what engineering is all about, the design cycle, including ideas, prototyping, using it, breaking it, and figuring out how to make it better, over and over again.”